A Boutique Automaker’s Custom, One-Off Designs Answer the Question “What If?”

Driven by creativity.

-

CategoryArtisans, Makers + Entrepreneurs

-

Written byShaun Tolson

-

AboveJonathan Ward with one of ICON's FJ Series vehicles

There’s an old adage that timing is everything. There’s also a belief that the best things in life are worth the wait.

There’s an old adage that timing is everything. There’s also a belief that the best things in life are worth the wait.

Both things can be true, as evidenced by the custom vehicles that Jonathan Ward painstakingly designs, engineers, and builds through the concepts division of his automotive company.

About 15 years ago, Ward launched Icon, a specialty vehicle enterprise that was conceived to both restore and modify classic Toyota FJ Cruisers. Those classically styled utility vehicles proved so popular that Ward added a second model, the Icon TR—a Driftmaster based on vintage 1947 and 1950 Chevrolet Pickups—though it wasn’t long before Ward was securing the rights to build modified vintage Ford Broncos, too.

In the beginning, Ward focused on one design package for those vehicles—a more modern, “new school” aesthetic that didn’t try to hide the fact that these vehicles were contemporary interpretations of classic automotive styling built from the ground up. More recently, Icon unveiled a second design package—an “old school” aesthetic that introduces enhancements and improvements in discreet packages that are, as Ward acknowledges, “a way to corrupt the purist.”

Regardless of their design package, these classically inspired vehicles are most impressive for what customers can’t actually see. “The way they drive and respond—the ergonomics and the performance—it’s almost counterintuitive to the aesthetic,” Ward explains. “It’s a shock, but in a good way.

“There are a lot of people that always had an appreciation for the classics,” he continues, “but the experience [driving a classic] won’t live up to the rosy eyes of memory. Within four or five miles, they’re disenchanted by it.”

Such disenchantment—felt by Ward himself—is what sparked the creation of an offshoot of the Icon brand that has since produced a rabbit hole of creative possibilities.

A couple of years into the business, Ward was in the market for a new car. Yet, a new car by traditional means wasn’t going to cut it. “New cars rarely hold my interest for more than couple months,” he says. “I don’t think there’s depth or soul to them. There’s no continuity in the design. However, I have found that I’m highly corrupted by the conveniences of modern cars.”

The solution to this quandary didn’t reveal itself until Ward visited an auto shop in Glendale and spotted a rotting 1952 DeSoto sedan—a car that Ward always believed had one of the coolest front clip designs of the 1950s. Immediately, he thought of a 1951 Chrysler Town & Country Wagon that he had found (and acquired) back in 2000. Ward bought the wagon more than two decades ago because he loved its body lines, as well as its interior design, but he loathed the look of its hood and front fenders. As a result, the car sat languishing in storage for years. The discovery of the DeSoto sedan—and Ward’s knowledge that both Desoto and Chrysler were owned by the same parent company—sparked a creative venture that finally pulled that wagon from its automotive purgatory.

A Dr. Frankenstein approach that Ward implemented in piecing together aspects of both of those early-1950s vehicles was done with a wabi-sabi influence—a Japanese world view rooted in the acceptance of transience. After two years of work, the resulting car sported a fuel-injected 500hp HEMI V8 engine under the hood; it featured a 6-speed automatic transmission; and it was integrated with a modern electrical system through which modern movements are hidden behind stock patina gauges. “The goal was to create something respectful of the original design values, keeping the brilliant patina, and hiding a modern chassis and design elements focused on modern performance and utility,” Ward explains.

That 1951 DeSoto Wagon, which became Ward’s daily driver, was branded Icon’s first Derelict, a new grouping of custom-build projects that reimagine timeless classics for modern use. “It’s just another way of revisiting transportation history in a modern concept,” says Ward.

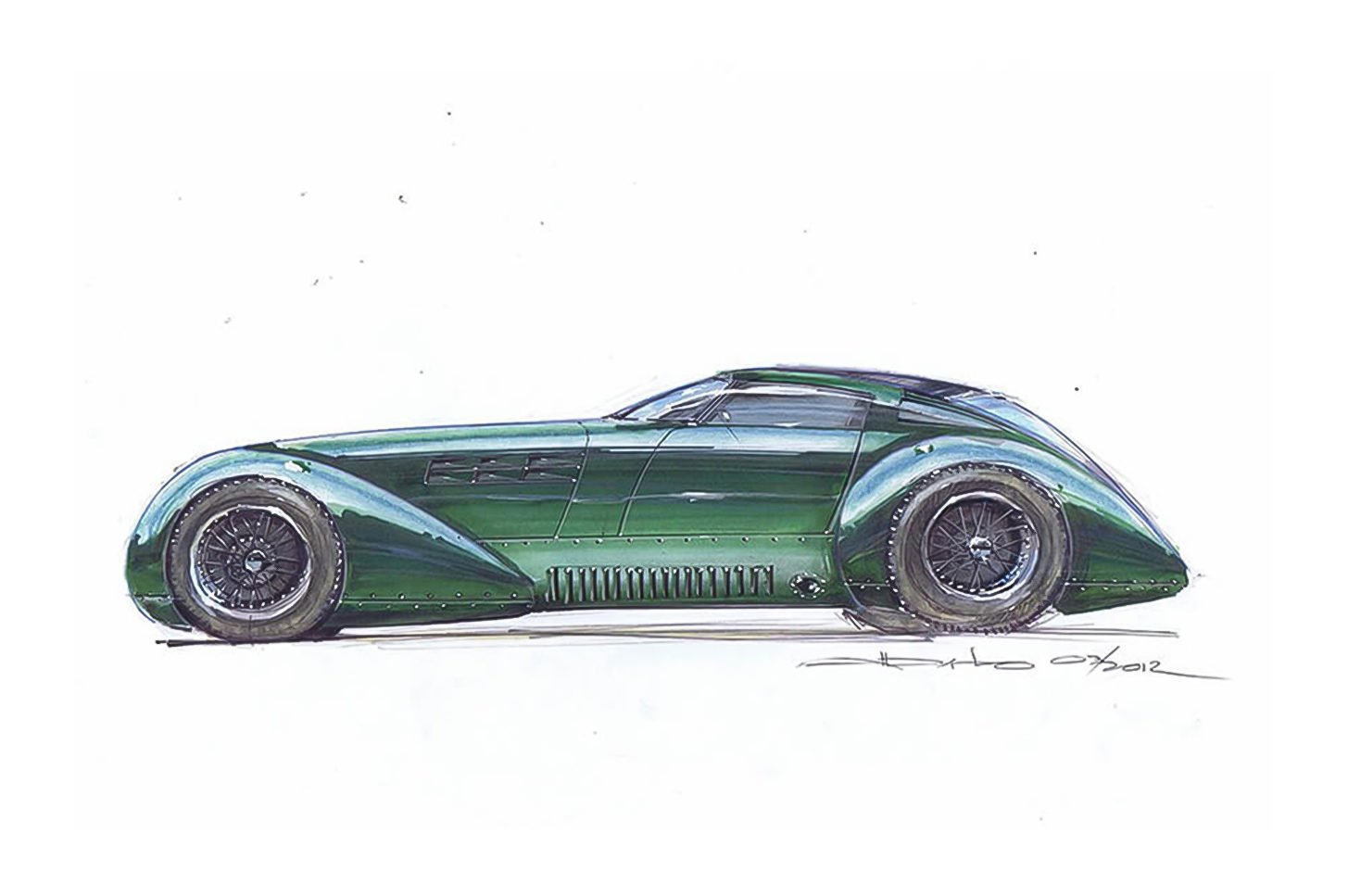

ICON Helios F34 Rendering

Since that wagon was completed, Icon has built and sold almost 20 subsequent Derelicts, but a concepts division was also established about five years ago—a separate department that builds singular, bespoke vehicles. Ward’s commitment to that division was influenced by two factors. First, it afforded him the possibility to scratch a creative itch that the established lineup of production Icon models couldn’t satiate. It also filled a vacancy in the automotive marketplace for specialty coachbuilders now that many of those storied brands already are—or are going—out of business.

“It seemed weird to me that all these [coachbuilding] companies were going away at a time when the technology was better,” he says, alluding to developments like laser scanning, 3D printing, and Cad Cam software that make the creation of specialty parts more viable and more accessible. “There is a perfect storm of assets and resources to allow that industry to stay strong and, in essence, grow.”

The inspirations behind the concept vehicles that Ward takes on are largely theoretical. What if the industrial revolution never prioritized quantity over quality? What if Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a pioneer of modernist architecture, was a member of the design team for the 1970 Plymouth Superbird? What if Bentley had built a hot rod during the 1940s? What if the Streamline Moderne design language had continued to flourish, instead of being snuffed out due to World War II and mass-production priorities? Those are the kinds of questions that Ward ponders, and the concept vehicles that he designs and builds for customers who share that same automotive enthusiasm and curiosity are his attempts to answer them.

Bentley Salt Flat Roadster Rendering

The opportunity to move around between different eras or origins of the design perspective, it’s so free-form,” Ward says of the work that his concepts division affords him. “It’s just constant discovery and constant expansion of my knowledge of history and my sense as a designer.”

While a sense of imagination and wonder are critical characteristics that any commissioning customer must have, an Icon concept vehicle requires patience above all else. Projects that start with a vintage donor vehicle typically require at least 14 months and sometimes as many as 32 months to complete, while more imaginative builds that begin with nothing more than a preliminary sketch most often demand four to five years’ worth of work. On top of all that, Ward is currently looking at about a 3-year wait list.

Not surprisingly, interested buyers who have the time (and patience) to wait must also have deep pockets. Icon’s one-off vehicles start around $500,000, while more complicated projects that conceptualize a vehicle from the ground up can reach a delivery price of $1.6 million. “As crazy as those price points are, they’re not good business,” Ward acknowledges. “They’re still profitable, but we’re talking about a net margin of about 5 to 8 percent if everything goes well.

“For providing us with that creative outlet, and for defining our capability and communicating the depth of our brand as a differentiator, they’re priceless,” he adds. “But they wouldn’t support a business by themselves.”

The Library Sessions: RIVVRS

Raised in Northern California and now living in LA, RIVVRS warmed up for his US tour at the Golden State office for an installment of The Library Sessions.

Thoughtful Tips for Incorporating Cannabis Into Your Home Landscape

Potted pot, scent gardens and other creative growing recommendations.

Get the Latest Stories